Edward Timothy Whittaker’s creations discovered

Story by R. K. Sawyer, for Lone Star Outdoor News

Copyright 2020 Lone Star Outdoor News . All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Collectors of Texas carved decoys always seem to work a little harder than their counterparts in other states. Many decoys have been lost to history during floods and hurricanes. And, because the Lone Star State’s carving and painting style are often not as refined as those from other regions, they haven’t always received the attention they deserve. In the Matagorda Bay area, for example, there were hints of a once fairly prolific carving culture, yet no one could find any decoys or even the names of the carvers.

Until now.

For years, Lone Star Outdoor News’ founder and dedicated Texas decoy collector David J. Sams printed a small advertisement that read “Decoys Wanted – Wooden.” Most folks who called him had no idea what kind of decoys they’d just discovered in their attic or barn, and Sams had to dash their dreams of a priceless or historical find. But as he rummaged through Port O’Connor’s Tim and Theresa Whittaker’s barrels of decoys, Sams said, “I recognized there was a difference in some and knew there was something there.”

Sams anxiously awaited, he said, “the Ron Gard approval.” Gard is the former senior consulting specialist to Sotheby’s American Folk Art Department and is an essential resource to anyone trying to identify Texas decoys. Gard was as excited as Sams. Not only did the Whittaker’s have a few decoys carved from the Matagorda Bay region, they knew where they were made — the US Coast Guard Saluria Station at Pass Cavallo on eastern Matagorda Island — and who carved them — Tim’s grandfather, Edward Timothy Whittaker.

The precursor to the US Coast Guard started building and manning lifesaving stations in Texas in 1878, their wooden frame buildings dotting the coastline from Sabine Pass to Brazos Santiago. One or more men were as- signed to each shift, and their job was to search for signs of shipwrecks from a watchtower. If a ship foundered, they dashed down the beach in horse- drawn carts loaded with equipment to attempt a rescue. A crew of rowers — surf- man — launched surfboats, often in furious storms. Theirs was a job filled with moments of terror, followed by weeks to months of stifling boredom. During these times, some lifesavers carved decoys.

History has not been kind to Texas decoys carved on its barrier islands. Only a handful of the wooden decoys John G. Mercer made when he was posted at the Port Aransas lifesaving station remain. Farther up the coast, Carlos Smith recalled that, as a boy, his family in Port Lavaca had a decoy spread that was “carved between shipwrecks” by the men at the Saluria lifesaving station. After the Smith’s lost those wooden blocks to Hurricane Carla, no known examples of the Saluria carvers were thought to remain. The missing pages on Matagorda Bay area decoys, however, have now been filled by the Whittaker’s.

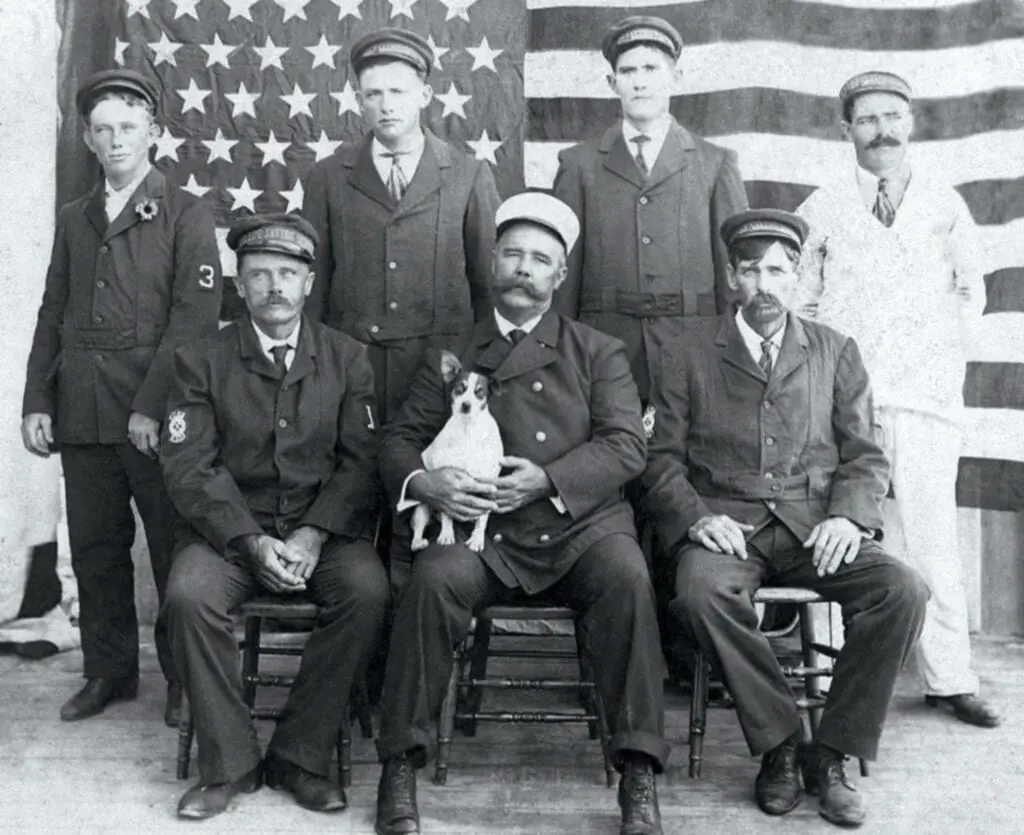

Edward Timothy Whittaker was born in 1878 in Point Isabel, Texas. After his father died when he was 10, he and his older brother George supported the family by working on the water. They saved enough money to buy a sailing craft, the Betsy, to tong oysters, and opened a fish, game, and oyster house in Alligator Head, later renamed Port O’Connor. In 1901, Edward enlisted at Saluria Station as a “Surfman,” living at the remote outpost for the next 20 years. He was joined in 1913 by his bride, Theresia Annie Schuster, and their son, Raymond, was born at the station two years later.

Theirs was a spartan existence at Station Saluria. Food was grown, caught, trapped and shot. Drinking water was collected in a cistern. They leased a cow for young Raymond’s milk, and the clothes he wore were fashioned from flour sacks.

It is not known if Edward carved before moving to Saluria, but it is safe to assume his most prolific period was between 1901 and 1920 while he lived on the island. His blocks were fashioned using only hand tools such as a hatchet, knife and a hand plane. Tim, in fact, still has two of his planes, one that carries the lettering USLSS for the US Life Saving Service and another with USCGS engraved on the handle. He used driftwood collected on the beach and occasionally balsa, which was a popular flotation material in life jackets around the time of World War I. Edward produced decoy bodies with graceful lines and a rounded bottom, but with a practical head design that sat low on the body and had a thick neck and bill.

To position the lead keel, Edward put his blocks in the water and watched how they floated, then attached the weight wherever he thought it would best balance. As a result, the keels are sometimes off-center. Tim remembers shooting over his grandfather’s deeks as a boy, and how “they floated naturally.” Most of the remaining Whittaker decoys have been re- painted — not surprising, as they were working decoys for over half a century.

Tim is the keeper of a few of the remaining family duck hunting stories. One passed down to him, over a hundred years ago now, was how his grandfather climbed the steps to the watchtower to scout birds, the next morning hunting wherever he saw the ducks go. After the family relocated to the mainland, he and Raymond hunt- ed Boggy Slough near their house on Washington Blvd., or “potshot” local ponds. Three generations of Whittaker’s hunted over Chesapeake Bay retrievers. Three generations have also hunted over the wooden decoys carved by Tim’s grandfather — Edward Whittaker.

Edward was 54 years old when he died of a heart attack while working at the Galveston Life Saving Station. He was buried in Old Town Cemetery in Brazoria County, where he was joined by his wife 42 years later.